Organizing of the training week

How many times per week should you squat? How often can you train the lower back? Should you do crunches every day? And what about that dreaded c-word? No, not that one you perve, I mean cardio. Today we won’t talk about that but we will delve deeper into how to organize a typical training week.

There is of course no short answer to all of this as it depends on several factors, for instance: what you are training for, what system of training you’re using, what type of long-term periodization you’re using or not using for that matter. But there are a few underlying factors that we can start to discus even without these premisses.

There should be an underlying goal for the week. This goal should in some way help you get closer to the larger goal (that is to say, what you’re actually training for). The goal in question can for instance be a new personal best in a particular lift or a repetition goal. The goal can also be part of an intermittent goal, for instance you might spend this and subsuquent weeks training to achieve that previously mentioned personal best or repetition goal. Other types of goals might be to get back into lifting heavier weights after a period of not lifting at all.

The structure of the week should allow adequate recovery to perform the tasks set out to be done this week. If you have planned to do a certain amount of squats on Monday and squats again on Tuesday, the training must be planned as such that it’s actually possible to achieve it. For instance, it’s probably not a good idea to plan a new personal best on Monday and a second personal best on Tuesday as the recovery is unlikely to be sufficient. However, this shouldn’t be mistaken to mean that you must always be fully recovered. You can plan your sessions in such a way that the training load is very high on Monday and lower on Tuesday. In our squat example the squats may be near maximal on Monday but significantly lighter on Tuesday. Furthermore, if the load is auto-regulated there might not be any particular loads determined, meaning a maximum could in theory be done on both days, as long as it’s understood that it’s the maximum for those particular days.

Let me dwell a bit on the last statement made. The training of a particular week does not have to be balanced since balance can happen on a macro scale just as well. An example of this that any coach or competitor would be familiar with is the week of a competition. The load is typically significantly less than other weeks prior because the goal is to reduce fatigue and make sure that the sportsman is in the best possible shape. In that regard the training in that week is unbalanced (”too light”) compared to earlier weeks.

Intensity in the weekly cycle

An old way of organizing the week is by the use of heavy-, medium- and light days. I have written a whole article about it already, you might want to check it out if you’re not familiar with the concept. The TL;DR of it is that weeks, months and even longer periods can be divided into heavy, medium and light periods. The medium period is roughly 80% of the heavy and the light is roughly 60% of the heavy. The concept can be applied to volume, intensity or both. It’s a foolproof way to organize the training week. For example, your squats can have a medium day on Monday, a heavy day on Thursday and a light day on Friday.

You don’t have to use those exact percentages but the concept illustrates an important point: it’s usually not wise to go balls to the walls all the time. There are other ways to divide your lifts even with a higher frequency. You can for instance have a hypertrophy day where reps are high, a strength day where the reps are low but intensity is high, and a speed day where intensity is low or medium but the intention is to lift as fast as possible.

Here is one way of utilizing days with different foci. These are not meant to be copied, they simply serve as examples.

Another option could be to calculate from your 1RM and have a day around 70%, a day around 80%, and a day around 90%. In my book that actually means light, medium and heavy, but your opinion may differ.

While you certainly can lift maximal weights every day you must do so with the understanding that every day will not be the same maximal (thus auto-regulating the intensity or the load) and that you will live with constant fatigue that will hide your potential. Even in Ivan Abadjiev’s system, which was notorious for its high frequency and intensity, the expectations of what would be a maximal was not constant every day. Furthermore certain exercises, such as power snatch and power clean, were put in place to change the load compared to the full snatch and full clean.

From experience I’ve seen that two heavy sessions can typically be planned per week, with the possibility of a third but it’s a gamble. Indeed, this is in line with what others have seen before me. Zatsiorsky and Kraemer claims in Science and Practice of Strength Training that 72 hours is necessary for recovery between these sessions, while smaller loads require 48 hours and even smaller requires 24 or 12 hours. The 72 hours gives us roughly two such sessions per week. One study on weight trained basketball players seemed to confirm this. Westside Barbell uses two maximal effort sessions per week. In the Bulgarian system the heaviest day is Friday (known as control training) with Monday and Wednesday being rather similar. Again, the Bulgarian system is pushing it, which ties into what I said above about a third heavy session.

In addition I find that with two heavy sessions, two medium sessions are doable as well. If more sessions are added they need to be lighter. Study the pattern, one third is heavy, one third is medium, one third is light. I think this also explains why so many prefer to train four days per week – more is pushing it unless you go light, which isn’t usually what people like to do (at least not the people I know). Of course there’s no need to stick to exact percentages.

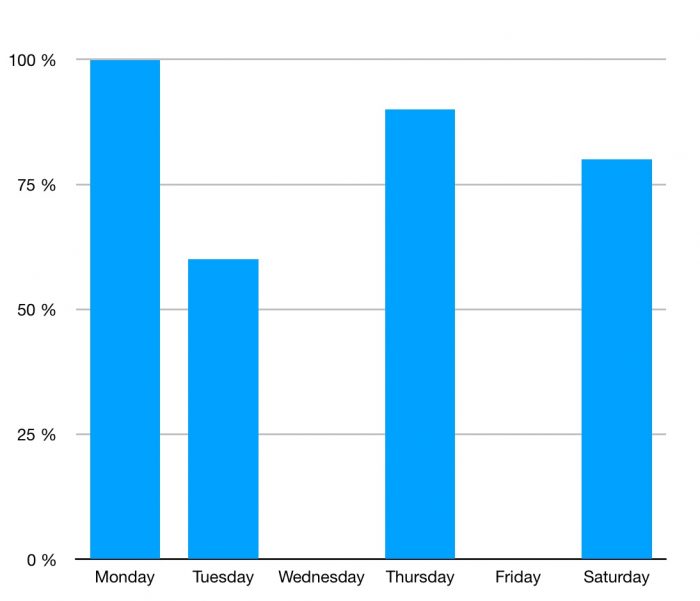

Here is one way to organize the week that breaks out of the exact 100%/80%/60% formula but note that the overall idea of it is there in terms of amount of days. The week starts with a heavy day (100%) after which it drops radically to a light day. After a day of rest another heavy day is used but this time around 90%. It’s no coincidence that it’s located 72 hours from the first heavy day. The fourth day is smack dab in the medium at 80%. This diagram isn’t intended to be copied, it just serves as an example of how one can play around with the parameters as long as the overall concepts stay intact.

The organizing of lifts in the weekly cycle

Until now I have avoided the discussion of utilizing a so called split routine, where either certain lifts or certain body parts are divided into their own days. While you most certainly can use a split routine, keep in mind that it’s by no means a given, it will depend on what your intent and goal is. If a lift is treated more as practice rather than training then it’s easy to see that doing it more often, as much as every day, will give you more of that practice. Many Olympic weightlifters snatch and clean and jerk in some fashion every day. Russian powerlifters are known to do their lifts on a high frequency basis too, essentially avoiding the old concept of squat on Monday, bench on Tuesday and deadlift on Friday. So do you want to practice your lifts or train your lifts? The question is a serious and important one.

The above will tie into your training system. If it states that you should push yourself to the limit every time (whether through intensity, repetitions or overall volume) then one is probably best adviced to take a split approach. For instance, going to the limit in squats on Monday will make it difficult to do the same on the deadlift that very day and certainly again the day after.

One need to pay attention to certain details about split routines. It’s easy to get into the false notion that since bench press is an upper body exercise and squat is a lower body exercise the two can simply be alternated without interfering with each other. This is certainly not the case because the fatigue generated from either of the two lifts aren’t localized to these areas just because you have decided to divide the exercises as such. A good lifter will for instance make good use of the back in the squat and the legs in the bench press. Furthermore the fatigue is systemic and not only local. Therefore one can’t assume that the body is rested enough for heavy training in bench press the day after heavy training in squat.

As a general rule of thumb, the more often you do a lift, either the volume or intensity or both will have to come down. This can to a point be overrided by the amount of other exercises that you do. Using the Bulgarian system again as an example, since the frequency of snatch, clean & jerk and squats are very high (daily) and the intensity is overall very high (close to or at maximum for most of the time) there’s simply no room to add many other exercises. In a traditional American-style powerlifting program where you might squat once per week, deadlift once per week and bench press once or twice per week there’s not only room for other exercises, they actually become necessary for overall volume to be enough in order to drive adaptation.

Deciding on focus and goals

Now that you know that intensity (the amount of weight lifted), the volume (the total amount of repetitions done), and frequency (how often a particular lift is done) can’t all be high you might ask yourself which you should focus on.

This is where we come back to what I mentioned in the beginning of the article – goal setting. Is your goal to increase strength endurance? Then more volume is likely to be the focus, thus causing intensity or frequency or both to come down. Realize maximal strength? Your best bet is to decrease volume and push intensity and possibly even frequency.

To an extent I believe this is where the biggest differences in training systems come in. While all the different strength systems might have the same end goal (increase maximal strength) the smaller goals to get there are different. One system might favor repetition maxes, another the perfection of skill for instance.

I will get back to the topic of goals another time because I feel it’s a topic most trainees and coaches don’t pay enough attention to.

In conclusion

As you have seen there are no steadfast rules to either frequency, intensity or volume but all three play by each others rule. Ultra high volume doesn’t mix with ultra high frequency and ultra high intensity. Something has got to give. If one or two of these factors are very high, the other must be lower. You can, generally speaking, have up to two of each at high peaks at the same time.

For a more balanced approach it’s useful to vary either the intensity or the volume over the course of the week. A good rule of thumb is that within systems where each lift is done more than once per week you can make use of two heavy days, two medium days and two light days – in that order. Meaning that if you plan the training for four days then light days may not be necessary, if you add a fifth day then it should be lighter. By the same token if you only train twice both days need to be heavy.

There are exceptions to the above guidelines, for instance so called stress cycles, but these are among the things we will look into in the next installment.